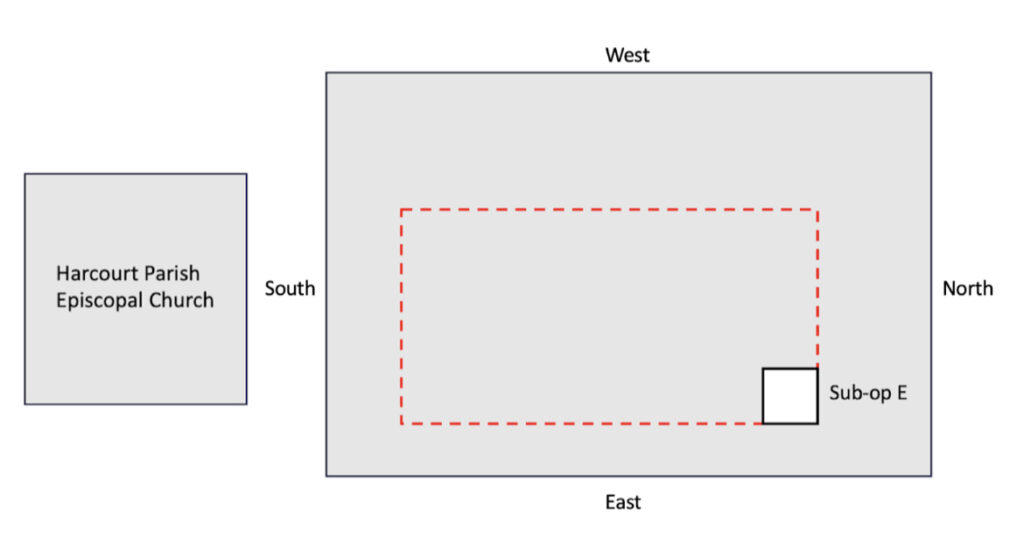

For the past few weeks, we have been excavating 1×1 meter units along what we suspect is the perimeter of our structure’s foundation. My specific sub-operation, sub-op E, is towards the southeast of the site (Figure 1). Our current goal is to reach the foundation. We hypothesize that the floor of our structure consisted of wooden planks laid on top of flat stones. The wood may have decomposed, but the stone foundation would have remained mostly intact. Thus far, we have peeled back the lawn from our excavation unit and scraped and pick-axed our way through a layer of fill dirt and stones placed on top of our structure. Artifacts in the fill layer were sparse, but in recent weeks, we have hit a much higher density of artifacts, meaning we are closer to finding the stone foundation.

Figure 1. A rough diagram of our excavation site. The site is 15 x 20 meters. Foundation of the structure detected with ground-penetrating radar is shown in red. Sup-operation E is shown in white. Other sub-operations are not shown. The diagram is not to scale.

Among the most common artifacts we have been finding in our sub-operation are nails (Figure 2.). We have found a variety of shapes and sizes of nails used in our structure. There are three kinds of nails typically found in American building

Hand-wrought nails

This kind of nail is made by pouring iron into a mold and hand-hammering it into its final shape. It is characterized by a taper on all four sides and a wood-like grain (Wells 1998). This type of nail has been used for centuries and remained in frequent use until the late 19th century. In the 1820s and 30s, when our structure was most likely built, both cut and wrought nails were in frequent use (Nelson 1968).

Cut nails

Cut Nails first appeared in the United States on a large scale after the Revolutionary War. There was a heavy overlap of hand-wrought and cut nails between 1790-1830. These nails were cut from one large, flat sheet of metal and can be distinguished from hand-wrought nails by their taper: only two sides of the nail are tapered, while the other two remain flat (Nelson 1968).

Wire nails

These nails are most commonly used today. They have long, cylindrical bodies with a four-facet point. They are held by a gripping device and headed, then sheared. This gives them a distinctive gripper mark towards the head of the nail (Nelson 1968).

Manufacturers of wire nails in the US started popping up in New York around the 1850s, but this variety of nail was not commonly used until the 1890s. Finding this kind of nail at our site would imply additions to the structure long after the initial construction in the 1820s (Nelson 1968).

Figure 2. Sample of nails found at sub-operation E of Bishop’s Cabin archaeological excavation. The scale bar is in centimeters.

Along with an abundance of nails, we have also uncovered two screws (Figure 3.) and several metal balls and longer metal pieces, which I haven’t photographed (but am very excited about). Once we switch to the laboratory analysis phase of our investigation, we can clean and analyze our artifacts more closely. Although nail chronology is one way to date an archaeological site, using ceramics and glassware can give a more reliable sense of time (Wells 1998). It would still be useful to see if we can glean information on the time during which construction or renovation of the building occurred. Combining this information with documentary records could give us a sense of when and where these nails were being made.

Regardless of what information we end up getting from them, the nails have been one of my favorite finds so far. Picturing them in the hands of workmen putting down planks two hundred years ago while holding them rusty and bent on Friday afternoons in 2023 makes me feel connected to the past in a way our other artifacts haven’t.

Figure 3. Slot-headed screw found at sub-operation E of Bishop’s Cabin archaeological excavation. Scale is in centimeters.

References:

Nelson, H. Lee

1968 Nail Chronology: As an Aid for Dating Old Buildings. History News Technical Leaflet,. Nashville, TN: American Association for State and Local History. pp 24-1.

Wells, Tom

1998 Nail Chronology: Technologically Derived Features. Historical Archaeology, Vol. 32, No. 2 , pp. 78-99

Leave a Reply